The last time I read — or rather, heard — something about filters that really grabbed me, it was Clay Shirky's talk: It's Not Information Overload, It's Filter Failure. And certainly, with the huge amount of information at our fingertips, we need to make filtering decisions all the time: What will we pay attention to, and what will we ignore?

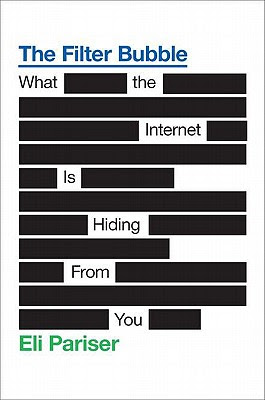

But what happens when filtering is going on, and it's invisible to us — and sometimes out of our control? That's what Eli Pariser addresses in The Filter Bubble.

Pariser agrees that we are "overwhelmed by a torrent of information" leading to "what blogger and media analyst Steve Rubel calls the attention crash." Pariser continues: "So when personalized filters offer a hand, we're inclined to take it."

And we've "always consumed media that appealed to our interests and avocations and ignored much of the rest," he says. The difference, according to Pariser, is that now we each have our individual one-person bubble, it's largely invisible, and it's not something we make a conscious choice about entering.

Did you realize that when you search on Google, your search results are being personalized — so what you see quite likely isn't what I see? You can disable at least much of this personalization, but I'll bet most people don't do this. (I actually did do this once upon a time, and then found I was annoyed when Google Maps didn't remember any of the locations I had searched for in the past. So exiting the bubble takes at least a small toll on efficiency.)

Did you know that your Facebook newsfeed may have been altered to only "show posts from friends and Pages you interact with the most"? Again, this is something you can control — but how many people know this is an option?

While personalization can help us manage our time, directing us to the things we care about the most, it also has some implications which are not so positive. As Pariser writes:

Democracy requires citizens to see things from one another's point of view, but instead we're more and more enclosed in our own bubbles. Democracy requires a reliance on shared facts; instead, we're being offered parallel but separate universes.And with filtering, we're less likely to have the moments of serendipity, where we stumble upon things we never would have known to search out. Again, quoting Pariser:

In the filter bubble, there's less room for the chance encounters that bring insight and learning.Pariser argues that the companies who control what we see have an "enormous curatorial power." Here's one of his questions related to Google:

If a 9/11 conspiracy theorist searches for "9/11," was it Google's job to show him the Popular Mechanics article that debunks his theory or the movie that supports it?He also points out that some web services do indeed let us control our filters:

Twitter makes it pretty straightforward to manage your filter and understand what's showing up and why whereas Facebook makes it nearly impossible. All other things being equal, if you're concerned about having control over your filter bubble, better to use services like Twitter than services like Facebook.Since reading this book, I've been thinking a bit more about who I follow on Twitter, trying to ensure I'm seeing diverse voices, while still avoiding an overwhelming number of voices.

If you want to learn a bit more about the filter bubble concept, without (or before) picking up the book, here are some web resources:

- The Filter Bubble TED Talk

- 10 Ways to Pop Your Filter Bubble

For some other reactions to the book, you can read:

- David Karpf's thoughts

- The discussion on MetaFilter

Finally, here's a little organizing-related quote I found buried in this book, where Pariser quotes Scott Heiferman, the founder of MeetUp.com:

"We don't need more things," he says. "People are more magical than iPads!"